![IMG_3690[1]](https://pamchernoff.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/img_36901-e1466897758704.jpg?w=132&h=300) Wedding planning was my first real hint that I would find meaning in the sensibilities and rituals of Judaism.

Wedding planning was my first real hint that I would find meaning in the sensibilities and rituals of Judaism.

Protestant wedding ceremonies tend to be short and to the point. They reflect a low-fuss sensibility that I internalized as I grew up. I associated ritual with the more formal and ornate services of Catholicism or its closest Protestant relative, Episcopalianism. That kind of formality both of worship and of setting wasn’t something I had ever craved.

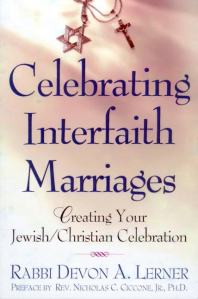

I had never even attended a Jewish wedding, so to help us figure out what traditions we wanted in the service, we bought “Celebrating Interfaith Marriages: Creating Your Jewish/Christian Celebration” by Rabbi Devon Lerner, hoping the book would help us figure out how to structure a wedding co-officiated by a minister and rabbi. For page after page, it described traditions that spoke to us—that symbolized things we wanted in our life together. We wanted our wedding day to be a meaningful reflection of the life we envisioned—not glossy perfection, but a full life surrounded by people we cared about. As we read and talked, I realized how hungry I was for rituals and symbolism that would give the day the weight it deserved.

I was 34 when we got married. I was deeply in love and sure I was making the right decision, but I wasn’t some starry eyed kid taking her turn being fairy princess for a day. We were adults with a sense of seriousness about the occasion. It was my first marriage, but Joel’s second. Both of us had long since lost the sense that we were exempt from life’s storms.

The Jewish traditions acknowledge that hard times come and that some decisions affect everything that comes after. They expressed how I felt—like someone taking a big step into the unknown, hoping for a smooth happy life but understanding the texture of life as it’s lived. The joys, yes, but also the times that make you cling to each other, too. The line from our vows that I still find most poignant is, “Loving what I know, and trusting what I do not yet know.” “Trusting what I do not yet know.” The perfect description of a leap of faith. Life will unfold. We will learn more about each other and about ourselves. And yet we trust what we have enough to promise to face it together.

In our planning, we were freer from parental expectations than many. My parents are committed to letting their adult daughters live our own lives and were happy to let us decide how we wanted the ceremony to be. Joel’s mother died many years before I came along, and his father approved.

Even though we were living in Northern California, we chose a wedding location in Virginia near Joel’s father, who was too old and frail to travel. Most of our relatives were either from the East Coast or Midwest so they were going to have to travel no matter where we got married. We didn’t know many people in California yet, and our friends were scattered around the many places we’d both lived. Having the wedding near the one parent who couldn’t travel to get there was a no-brainer.

Our hunt for just the right venue took us through a coldly modern private club favored by our wedding planner, assorted hotel ballrooms, and a restaurant where the staff illustrated its disdain for us and our budget by describing a wedding in which the groom rode up on an elephant, a Hindu wedding tradition. While I would someday love to hear the logistics of getting an elephant onto the Georgetown waterfront, the place clearly wasn’t right for us.

We ultimately chose a simple but elegant Unitarian church where the light filtered down from the skylight and an estate on the grounds gave the reception a homey feel. Because Unitarianism is pluralistic, worship spaces are not decorated with religious symbols. There weren’t any crosses on the walls or other potentially problematic iconography to be argued over or strategically covered. Just a warm, inviting space infused with natural light.

As we worked through what we wanted, it became clear that we didn’t need a minister to co-officiate—that having just a rabbi would be fine, a decision that I did not find particularly fraught given my affinity for the traditions we were embracing.

For many interfaith couples, finding a rabbi to officiate is a painful step. Some Reform rabbis won’t perform interfaith weddings, and the Conservative movement prohibits rabbis from officiating at them. This can be a moment for a painful conversation with a beloved rabbi who feels prohibited from presiding over the ceremony either by conscience or by the dictates of his or her movement.

The sheer percentage of American Jews who intermarry means that most Jewish movements have had to assess and reassess how they address intermarriage at the time of the wedding and what boundaries they set for interfaith families. In 2013, a study by the Pew Research Center found a 72% intermarriage rate among non-Orthodox American Jews who married between 2000 and 2013.

Sometimes the rabbi who can’t or won’t perform the ceremony will offer up the name of a rabbi who will, sometimes the rabbi will discourage the union altogether. And sometimes the discouraged couple will hear, “I love you but I can’t,” and sometimes they’ll hear, “you aren’t welcome here.” This moment can be the start of a conversation or the end of an attempt to engage with Judaism.

We were lucky. We weren’t leaving out my favorite minister or being told “no” by Joel’s favorite rabbi. Our wedding planner gave us a list of rabbis who would officiate at interfaith marriages, which led us to a rabbi for a Humanistic Jewish congregation—one that practices the rituals of Judaism from a non-theistic perspective—who was willing to perform our Friday early evening wedding ceremony. It was July so the sun wasn’t down yet, but that timing—on the cusp of the Sabbath—is one of the few things I might change about the day if we were to do it over again.

The rabbi was very experienced with interfaith weddings. He carefully and clearly described the meanings behind the traditions in the ceremony so that everyone felt included. Although his congregation was Humanistic, he did not have a problem with including God language in the service—something that wasn’t negotiable for me.