India was a blessed nation for thousands of years, it has had a good history of Pluralism and inclusion, all that is changing now with the right wing government who do not tolerate interfaith marraiges and carry out harassment and even killing. All this will change, badness never lasts.

Mike Ghouse

Wedding Officiant

Mike@Interfaithmarriages.org

# # #

Opposition to interfaith marriage in India puts many couples at risk

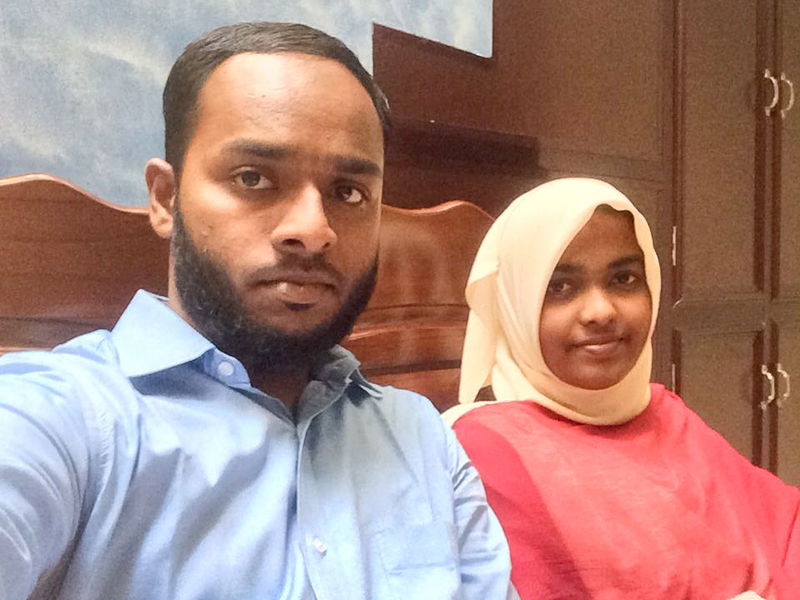

Hadiya, right, converted to Islam to marry Shafin Jahan. Their marriage has been the center of a large court case and referred to as “love jihad.” Photo via Twitter

In December, when the couple was out at a nearby mall, some men — suspected by the husband to be acting at the behest of his in-laws — picked up his wife and drove off with her in a car.

He registered a fresh case with the police and then filed a petition in the Bombay High Court through his advocate Hasnain Kazi, seeking that his wife be returned. They were reunited in early February, and her family has now started to come around.

“This is a family matter. Society shouldn’t interfere,” said the husband. “But political leaders have created an atmosphere that has affected our personal lives.”

Such incidents are part of a wider pattern in India, where interfaith and intercaste couples are increasingly facing bullying, harassment, familial opposition and even death threats.

Ankit Saxena. Photo via Twitter

In February, a Facebook page calling for violence against more than 100 Muslim men who had married or were dating Hindu women was taken down after an online outcry. The same month, Ankit Saxena, a Hindu man, was killed in Delhi, allegedly by relatives of his Muslim girlfriend. Some of the alleged assailants were arrested later. In December, Hindu right-wing groups barged into an interfaith wedding celebration just outside Delhi. Such incidents have consistently been reported across states including Madhya Pradesh, Kerala and Uttar Pradesh.

Interfaith and intercaste couples have never had it easy in India, but since the Bharatiya Janata Party was elected in 2014, the atmosphere has become increasingly polarized. Government data recently made available in Parliament show that the number of incidents of interreligious violence in 2017 (822) was higher than in 2016 (703) and 2015 (751). These increases have been accompanied by growing anti-Muslim rhetoric.

“Since the coming to power of the BJP there has been lots of talk about religion and caste,” said Rajpalsingh Shinde, a Nashik-based lawyer who has helped more than 200 interfaith and intercaste couples get married. “The atmosphere has become very divisive.”

Shinde, a Hindu who faced opposition when he married a Buddhist, said anti-Dalit sentiment has also intensified in the past few years. (Dalits were once considered the lowest social group and were called “untouchables.”)

“Many young people are getting frustrated,” he said. “Relationships are breaking, people aren’t able to oppose their families or society, they are getting depressed.”

Sometimes interfaith couples commit suicide, driven by the pressure. And in India, which continues to be a highly stratified society, “honor killings” in interfaith and intercaste marriages have been reported.

In 2016 a band of young people in Maharashtra started the Sairat Marriage Group to help interfaith and intercaste couples. More than 200 people have approached them so far, and they receive at least 10 calls a month seeking help or counseling, says convener Harshal Lohakare. “Our work has increased and our challenges have increased. Couples are more scared.”

Shafin Jahan and his wife, Hadiya. Their marriage was annulled and later reinstated by Indian courts. Photo via Shafin Jahan/Facebook

In 2016, in one of the most high-profile cases, a man from Kerala, KM Asokan, filed a missing-persons report after the disappearance of his daughter Akhila. When she appeared before the Kerala high court, she said she had changed her name to Hadiya and had chosen to convert to Islam and marry a Muslim man, but her father contended she had been indoctrinated.

Last May, the court annulled the marriage and handed over the daughter’s custody to her father. Though voluntary conversion is legal in India, it is often fraught with problems. Later the matter was taken to the Supreme Court, which set aside the annulment and ruled that Hadiya was an adult and the court couldn’t decide the validity of the marriage.

The case raised the specter of the “love jihad,” the claim by some Hindus that Muslim men seduce Hindu women in order to convert them to Islam. The term was first widely used in 2009 when the Kerala high court ordered an inquiry into whether there was a large-scale conversion campaign. Police reports said that was not the case, but the phrase has in the past few years acquired a renewed currency.

“Ever since 2014, the issue of love jihad has been resurfacing,” said Pratik Sinha, co-founder of Altnews.in, which calls itself an anti-propaganda news site.

Altnews first published the story about the Facebook list on Hindu-Muslim couples on Feb. 4, and the page was taken down soon after. “During volatile times, these kinds of lists can be misused and people targeted,” said Sinha.

Earlier this year, the Supreme Court of India said no one could interfere in a marriage between two consenting adults, while admonishing khap panchayats, or community groups that operate as quasi-judicial bodies and often rule on marriages.

In an earlier judgment in 2011 the court had recommended suspension and investigation of high-ranking officials who failed to act against the perpetrators behind so-called honor killings.

“We sometimes hear of ‘honor’ killings of such persons who undergo intercaste or interreligious marriage of their own free will,” it had then said. “There is nothing honorable in such killings, and in fact they are nothing but barbaric and shameful acts of murder committed by brutal, feudal-minded persons who deserve harsh punishment. Only in this way can we stamp out such acts of barbarism.”

But according to Sanjoy Sachdev, the chairman of Love Commandos, a Delhi-based organization helping couples who want to marry for love, these directives were never taken seriously by any major party. “Political parties are not concerned about love,” he said. “The BJP gives election tickets (the opportunity to be candidate) to khap panchayat leaders. The Congress party says khaps are part of our culture.”

Love Commandos says it has helped thousands of couples since 2010 and provides legal help and shelter for those who need it.

The group has faced threats, but Sachdev sounded undeterred. “We want to shun violence with nonviolence,” he said. “We want to make this a people’s mission.”

For some though, there might be happy endings despite the strife.

“When my wife’s brother found out about us, we got into a huge fight, because he said, ‘What will people say?,’” said Nitin Kasar, 22, a man from the dominant Maratha caste group, who married a woman from a different caste last year. “We knew people would have difficulty accepting an intercaste union. But our families have gradually come around.”